Paper: “'A combination of everything': a mixed-methods approach to the factors which autistic people

consider important in suicidality"

This paper was published in 2025, in the journal Autism in Adulthood.

The research was initiated, promoted and supported by charity Autism Action, whose number one priority is suicide prevention in autistic people. The authors were Dr Rachel Moseley, Dr Sarah Marsden, Dr Carrie Allison, Dr Tracey Parsons, Dr Sarah Cassidy, Dr Tanya Procyshyn, Dr Mirabel Pelton, Dr Elizabeth Weir, Ms Tanatswa Chikaura, Professor David Mosse, Dr Ian Hall, Dr Lewis Owens, Mr Jon Cheyette, Mr David Crichton, Professor Jacqui Rodgers, Ms Holly Hodges, and Professor Simon Baron-Cohen (author links will open in separate tabs).

You can click HERE to download the version of this paper which was accepted for publication (for copyright reasons, it's not possible to upload the journal's final formatted and printed version).

Please note that the full version of the paper may be triggering: it includes some distressing descriptions of suicidal thoughts and the experiences which led to them. Please take care of yourself; you may decide not to read it right now if you are in a vulnerable state.

Keep reading to see a less-detailed plain English summary, or you can watch my explanatory video!

Why is this an important issue?

Autistic people are more likely to die by suicide than are non-autistic people, and many live with the distressing burden of suicidal thoughts on a daily basis. To change this, we need to understand why suicidal thoughts and feelings are relatively common in autistic people, as well as why some end their lives.

Previously, researchers have tried to understand suicide in autistic people through the lens of theories (and using assessment tools) based on non-autistic people. This can be problematic, because our earlier work (here and here [links open in new tabs] ) shows that assumptions from theories about non-autistic people don't necessarily apply in autistic people.

No studies, to our knowledge, have asked autistic people about the factors which contributed to their suicidal experiences. This means that we are missing out on a vital source of information - one that could help us identify ways to reduce the number of autistic people who consider, attempt and die by suicide.

Here is a video summary of this paper. You can open it up to large screen, and turn captions on and off by clicking the 'CC' button. (Please ignore my speech impediment in places!)

What was the purpose of this study, and what did the researchers do?

We wanted to understand, from autistic people themselves, what factors contributed to their suicidal experiences. We also wanted to understand whether these factors were different in autistic people of different genders and ages. Lastly, we wanted to understand whether the contributing factors that autistic people identified were different in people with varying degrees of experience with suicide, thinking that this might tell us something about the risk factors that characterise people with more severe lifetime experience with suicide.

Working with the charity Autism Action and their advisory panel of autistic people and family members of autistic people, we designed an online survey, incorporating feedback from these advisors. It included many questions, such as about people's help-seeking experiences - we published these in a separate paper (click here to read these in new tab). In this paper, we focused on the questions asking participants about the factors which contributed to their suicidal feelings. Participants could choose multiple pre-entered factors based on suggestions from autistic advisors and previous research, and/or write in their own reasons. We looked at how often participants selected each pre-entered factor, as well as looking for themes (common views or ideas) in their free-text responses.

Almost 1400 (1369) autistic people took part in our study. Around 94% of them were from the UK, and almost 90% were white. About half (52%) were cisgender women, 24% were cisgender men, and 24% were had transgender and/or gender-divergent identities, or were unsure of their gender.

All of our participants had had some degree of experience with suicidal thoughts and/or suicide attempts: 10.2% had experienced brief passing thoughts of suicide, 22.6% had experienced prolonged and intense thoughts of suicide, 29.1% had planned a suicide attempt but not acted on that plan, and 38.1% had attempted suicide at least once.

What were the results of the study?

Part 1: The most important factors which contributed to suicidal thoughts and feelings

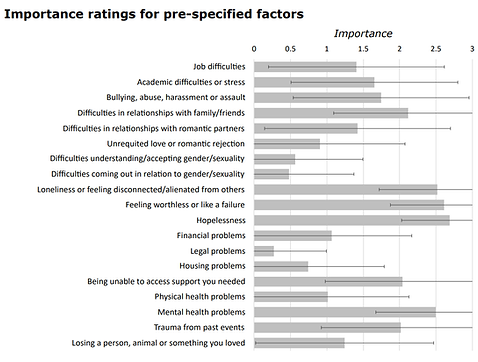

Of the pre-entered factors, the five factors with highest importance ratings were: difficulties with family and friends, loneliness, feelings of worthlessness or failure, hopelessness, and mental health problems. You can see how participants rated each factor in the image to the right.

Participants rated the importance of each of the below listed factors. They had to rate them between 0 ("not important or relevant at all") and 3 ("very important/relevant"). The image below shows the average importance ratings for each factor.

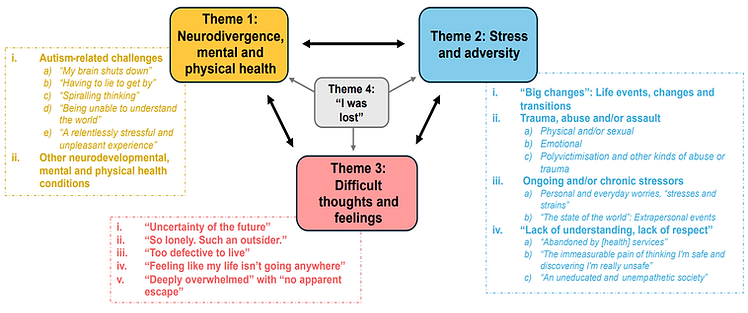

We looked for common 'themes' (i.e. messages or ideas) in participants' free-text responses to the question about what factors contributed to their suicidal thoughts and feelings. These are the themes we identified; some of them have subthemes (marked by roman numerals) and sub-subthemes (marked by letter numerals). To read participants' words in more detail, you can download the paper above.

In Theme 1, people linked suicidal thoughts to aspects of being autistic, like sensory, social and emotional overload, the exhaustion of masking, having 'sticky', black and white thoughts, and struggling to understand the world. They also linked suicide to the stress of being autistic generally, and to other health conditions and neurodivergence.

In Theme 3, people talked about some of the feelings underpinning suicidal thoughts. These included fears of the future (i); feeling lonely, alone, and disconnected from others (ii); feeling worthless and a burden to others (iii); lacking purpose (iv); and feeling trapped in overwhelming circumstances (v). Often, these mental states were linked with aspects of being autistic (Theme 1), with being undiagnosed (Theme 4), and/or with unpleasant life events (Theme 2).

In Theme 4, people talked about how being undiagnosed autistic had led to suicidal feelings. Often, being undiagnosed led to the feelings described in Theme 3, and/or led to some of the distressing life events of Theme 2. Being undiagnosed could also worsen some of the difficult aspects of being autistic described in Theme 1. As such, being undiagnosed contributed to suicidal thoughts in many ways.

In Theme 2, people talked about distressing life events that often gave rise to the feelings of Theme 3. These included major life changes, including biological transitions and life transitions (i); different forms of trauma, abuse or assault (ii); chronic (i.e. long-lasting) stress, such as everyday strains and global or national concerns out of your control (iii); and the stress of living in a society which does not understand or respect autistic people (iv). Within this last subtheme, participants talked about the stress of having insufficient support, and being victimised by people in positions of authority or responsibility (e.g. doctors).

Part 2: The contributing factors to suicide differed between autistic people of different genders and ages

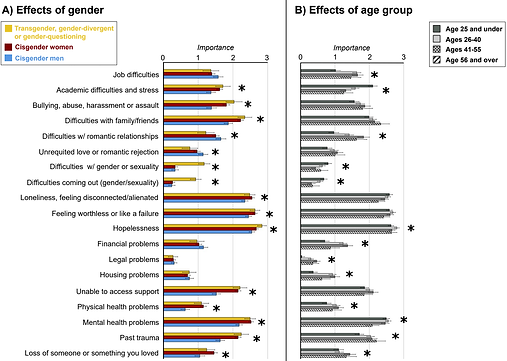

In contrast to men, autistic women and trans/gender-divergent participants highlighted

-

Academic difficulties and stress

-

Bullying

-

Difficulties with friends/family

-

Hopelessness

-

Being unable to access support

-

Physical health issues

-

Mental health issues

-

Past trauma

-

Loneliness (women specifically)

-

Worthlessness and feelings of failure (women specifically)

-

Loss (women specifically)

-

Difficulties accepting and coming out in relation to gender and/or sexuality (trans/gender-divergent participants specifically)

Men were more likely to highlight difficulties in romantic relationships and unrequited love.

Differences across age groups showed that younger participants were more affected by academic stress and gender-related challenges, and older participants were more affected by job difficulties, difficulties in romantic relationships, financial problems, legal problems, housing problems, physical health problems, and past trauma.

Autistic people in the 26-40 age group were more strongly affected by hopelessness.

On the left, you can see differences in how autistic men, women and transgender/gender-divergent or gender-questioning participants rated the importance of pre-entered factors: robust differences are marked by asterisks. On the right, you can see differences between autistic people of different age groups, with asterisks marking out robust differences.

We can link some of these findings to what other studies have told us:

Autistic women and sex/gender minorities are more likely to experience victimisation, abuse, mental and physical illness, and find it harder to access help

Autistic women are sometimes found to be more lonely, while struggling to manage friend/family relationships. Autistic sex/gender minorities are likely to experience additional challenges in their relationships

Support for autistic people drops as they go into adulthood, while challenges with employment and independence increase: hence greater hopelessness in the 26-40 age group.

The lack of differences in bullying and loneliness, across age groups, is consistent with the fact that these are problems for autistic people throughout their lives.

Part 3: We could predict autistic people's lifetime experience with suicide from how they rated these pre-entered contributing factors

We looked to see whether people's importance ratings for each pre-entered factor could predict which group they belonged to: those who had experienced only passing thoughts of suicide, those who had experienced more prolonged and intense suicide ideation, those who had made a suicide plan, and those who had attempted suicide.

People who had attempted suicide were marked out by having rated 'past trauma' and 'being unable to access help' as more important than any other group.

Rating 'Bullying, abuse, harassment or assault' as very important was characteristic of autistic people who had made suicide plans and those who had attempted suicide.

Where contributing factors failed to differentiate between people with different degrees of experience with suicide, it means that these factors affected everyone, regardless of their degree of experience with suicide. 'Mental illness' and 'hopelessness', for instance, were rated as less important by people with only passing thoughts of suicide, but were equally important for people with suicidal thoughts, suicide plans, and suicide attempts. That 'past trauma', 'being unable to access help' and 'bullying...' distinguished people with greater degrees of experience with suicide suggests that these factors might indicate who moves from thinking about suicide to acting on those thoughts. This could help us intervene to save lives.

What are potential weaknesses in the study?

We measured autistic people's perception of contributing factors as they were reflecting back on their lives. Because this study didn't measure actual exposure to these contributing factors, we can't be sure that these factors really were associated with later suicidal thoughts and behaviour. For instance, we can't tell if autistic people who rated 'bullying' as unimportant never experienced it, were less distressed by the experience, and/or perceived other factors as more important. This means we can't be totally sure that bullying does predict later suicidal behaviour.

Our study was very specific to the UK, and our autistic participants were not representative of autistic people with learning disabilities and higher support needs, or autistic people of colour, who might face additional barriers to healthcare.

Our comparisons were a bit unbalanced, since we had more autistic women than men and trans/gender-divergent individuals. As such, our findings might not generalise to all autistic men, or to people with specific transgender or gender-divergent identities.

Very importantly, there are some autistic people who experience suicidality but choose not to participate in online surveys or to seek help - we don't know anything about these individuals, or how many autistic people die by suicide without ever having sought help.

How will these findings help autistic adults now or in the future?

Our findings give us a window into the kind of thoughts and feelings which underpin suicidal behaviour in autistic people, and the kinds of experiences that give rise to those thoughts and feelings. This should help clinicians to understand the autistic people they work with, and better understand how to help.

Our findings suggest that the risk factors for suicide in autistic people differ by gender. This means that approaches to preventing suicide also need to be gender-sensitive.

Our findings suggest that certain life experiences might be especially associated with suicide risk: namely 'bullying, abuse, harassment, and assault', 'past trauma', and 'being unable to access help'. This highlights that more needs to be done to protect autistic people from victimisation and ensure they are listened to and can access help when they need it.

Thank you for reading!

If you found this interesting, you may like to read:

-

"'The best way we can stop suicides is by making lives worth living': a mixed-methods survey in the UK of perspectives on suicide prevention from the autism community" (2026)

If you are struggling with suicidal thoughts or your mental health, please look at the resources page in case there is something helpful there for you.