Paper: "Lifetime stressor exposure is related

to suicidality in autistic adults: A multinational study"

This paper was published in 2025, in the journal Autism.

The two lead authors were myself (Dr Rachel Moseley) and Dr Darren Hedley. Our co-authors were Professor Julie Gamble-Turner, Dr Mirko Uljarević, Dr Simon Bury, Dr Grant Shields, Professor Julian Trollor, Dr Mark Stokes, and Professor George Slavich. (author links will open in separate tabs)

You can click HERE to download a PDF of the paper.

This paper follows on from a previous one which you might like to read first (link opens in new window). When you are ready, keep reading to see a plain English summary, or you can watch my explanatory video!

Why is this an important issue?

Autistic people are five times more likely to die by suicide than non-autistic people. To change this, we need to understand why risk is so high.

We know from the general population that when we encounter life events that we experience as stressful (what psychologists call “stressors”), it sets off a biological stress response that can impact mental health and contribute to suicidal thoughts and behaviours (henceforth written as "STB" for short). Although we know about specific stressors that are associated with STB in the general population, little is known about the kinds of stressors that increase the risk of STB in autistic people. We also do not know if the stressors linked with STB in autistic people differ by gender.

Here is a short video summary. You can open it up to large screen, and turn captions on and off by clicking the 'CC' button.

What was the purpose of this study, and what did the researchers do?

To examine this issue, we catalogued the life stressors that autistic men and women experienced over their entire life course to date, and investigated how these stressors were related to STB.

We did this by pooling data that was collected in the UK (written about here) and data collected by researchers in Australia. We were able to do this because autistic people in the UK and Australian studies completed the same assessment: The Stress and Adversity Inventory (STRAIN). This is a comprehensive interview-based measure which provides a detailed picture of potentially stressful life events that have occurred across the whole life-course. It also measures how people feel or felt about that life event – as one person may perceive something as stressful while another may not (for e.g., going on holiday can be very stressful to some people and pleasurable for others), this is very important. You can read more about the STRAIN, if you want to, here.

Pooling the data across UK and Australian samples meant that we could analyse STRAIN data from 226 autistic adults. Most had been diagnosed in adulthood, and most identified as women (70%). First, we compared the mental health, suicidal experiences and lifetime stressor exposure of our male and female participants. Secondly, we looked at whether exposure to particular kinds of stressors, and perceived severity of particular kinds of stressors, were associated with STB in men and women separately.

What were the results of the study?

Comparing autistic men and women

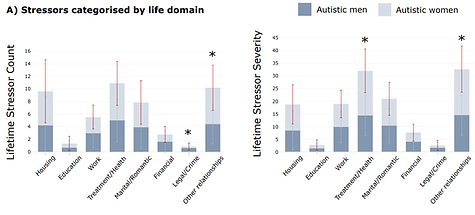

Autistic male and female participants had similar levels of current psychological distress (e.g. mental illness), and similar degrees of experience with STB. However, they were quite different in their 'stressor profiles', as you can see in the image to the right.

Comparing autistic men and women, we found:

-

autistic men had had more exposure to crime/legal-related stressors (e.g. being arrested, or being the victim of a crime). This is actually a 'normal' gender difference that we see in non-autistic people!

-

autistic women had more exposure to stress related to difficulties with family and friends (again a 'normal' gender difference).

-

autistic women found family- and friend-related stress more stressful than autistic men - i.e. they were more badly affected by these incidents when they occurred.

-

autistic women also found stressors related to health and treatment (e.g. seeking medical help) more stressful than did autistic men, though they were equally likely to experience these kinds of stressor.

If we look at stressors a different way...

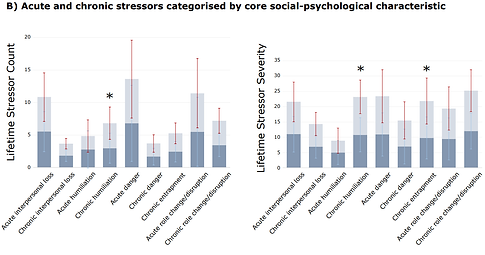

We can think about the mental or emotional states they are associated with. When it comes to suicide, it might be important to understand that stressors which might look a bit different on the surface, may give rise to similar emotional states. For example, we know that autistic people are more likely to be victimised across many spheres of their lives, including school, work, and even at home in intimate relationships. Therefore, it might be important to look at the mental states associated with stressors that happen in different areas of a person's life.

When we looked at stressors in this way, we found that autistic women experienced more stressors associated with feelings of chronic (i.e. long-lasting) humiliation (such as being bullied, being fired from a job) - and they found these humiliating stressors more stressful than did autistic men.

Autistic women also experienced chronic entrapment stressors as more distressing than did autistic men. Entrapment means feeling helplessly trapped in an inescapable situation: overwhelming responsibilities at work or home, overwhelming pressure from others, and being unable to escape poverty are all examples of entrapment.

The bar chart on the left ("Lifetime stressor count") shows the different kinds of stressor that autistic men (dark grey) and autistic women (light grey) were exposed to. The bar chart on the right ("Lifetime stressor severity") shows differences in how autistic men and women experienced these life stressors - e.g. how badly they were affected by them. The asterisks (*) mark out gender differences that were statistically robust.

The bar charts below show the different kinds of mental state measured by the STRAIN: feelings of loss (e.g. associated with bereavement), humiliation (e.g. associated with bullying), danger (e.g. associated with being attacked), entrapment (e.g. associated with overwhelming situations the person can't escape), and role change or disruption (e.g. associated with situations where a person's role changes: for instance, having to care for an elderly parent who has always supported you). The STRAIN measures 'acute' and 'chronic' instances of each of these mental state: acute means short-term events, while chronic means stressors that went on for a long time (e.g. being attacked might be an acute example of a danger stressor, while having a life-threatening illness would be a chronic example of a danger stressor).

The bar chart on the left ("Lifetime stressor count") shows that autistic men (dark grey) and autistic women (light grey) were differently exposed to these different kinds of stressor. The bar chart on the right ("Lifetime stressor severity") shows differences in how badly autistic men and women were affected by these stressors. As before, the asterisks (*) mark out gender differences that were statistically robust.

Which stressors were important for suicidal thoughts and behaviour (STB)?

-

Experiencing more treatment/health-related stressors, and perceiving these as more stressful, was linked to higher levels of lifetime STB. This was true for autistic men and women. This finding might reflect the fact that mental illness is strongly associated with STB, since people with mental illnesses are more likely to seek treatment, and hence encounter this kind of stressor. However, this finding might also reflect that experiencing more negative healthcare experiences when seeking help is associated with STB.

-

In autistic men, stressors associated with interpersonal loss (such as bereavement) were linked with higher levels of STB. This is consistent with findings that autistic men may grow increasingly isolated as they age and lose some of their social networks.

-

In autistic women, experiencing more acute physical danger stressors (e.g. being attacked or abused), and finding these more stressful, was linked with higher levels of lifetime STB. This might be due to trauma associated with these kinds of life experience.

-

In autistic women, experiencing fewer chronic entrapment stressors was associated with higher levels of STB. This was an unexpected finding. It might be that although chronic entrapment stressors are stressful - for instance, imagine a stressful job, or being a carer - they also act in some way as a form of connection to other people, or to give individuals a sense of purpose/meaning. As such, if you have fewer of these stressors, it might mean you are more isolated. This is just one possible interpretation. However, it seems to go along with our finding that autistic women who perceived friend/family difficulties as less distressing tended to have higher levels of STB - perhaps again reflecting that they had fewer such connections?

-

What are potential weaknesses in the study?

Because this study looked at a snapshot of participants’ current states, we cannot be sure that the stressful life events we measured actually preceded and contributed to STB.

We didn't include a non-autistic comparison group, so we can't tell if these relationships differ between autistic and non-autistic people.

Our sample was not representative of autistic people with intellectual disabilities, non-binary and trans autistic people, or autistic people of colour. Unfortunately, we did not have sufficient numbers of autistic people who identified as intersex, transgender and/or non-binary, so we looked at only men and women. This is especially important given that people with minority gender and/or sex identities are likely to experience more stressful life events than cisgender people.

Finally, our measurement tools, including the STRAIN, weren't designed for autistic people. That means that these tools might not capture experiences that are important to autistic people when it comes to suicidal thoughts and/or behaviour.

How will these findings help autistic adults now or in the future?

Our findings suggest that the risk factors for suicide in autistic people differ by gender. This means that approaches to preventing suicide also need to be gender-sensitive.

Our findings suggest that a person's "stress profile" is highly relevant to their risk of suicide. This means that asking autistic people about their history of stress exposure could be important for understanding their suicide risk, their unique 'triggers' or risk factors, and understanding the most appropriate ways to help.

Our findings highlight certain stressors as possibly more relevant to suicide risk - such as treatment/health-related stressors. We need to understand more about these stressors, for instance whether they reflect negative encounters when seeking healthcare - our later work (link opens in new window) suggests that feeling unable to access help is indeed an important risk factor for suicide attempts.

Thank you for reading!

If you found this interesting, you may like to read:

-

"'A combination of everything': a mixed-methods approach to the factors which autistic people consider important in suicidality" (2025)

If you are struggling with suicidal thoughts or your mental health, please look at the resources page in case there is something helpful there for you.